When Xi Jinping revealed his first big policy manifesto after taking the helm of China’s Communist party, he electrified the world of global finance with a call for state-owned enterprises to step back and let markets play a “decisive” role in the world’s second-largest economy.

Analysts at Goldman Sachs hailed the slate of policy priorities, released in late 2013, as a “bold economic reform agenda” with a “pro-market stance” that would curb government intervention and rein in entrenched state-run businesses.

But in the years that followed, waves of volatility in Chinese stocks and currency, the threat of financial disruption from upstart tech tycoons and fears offshore listings could breach data security only served to bolster the case among policymakers that if markets are to play a “decisive role”, then the role of the party must be more decisive still.

“[China’s leaders] think they know better than the market and many of [their] actions have done real damage to it and to the economy,” said Weijian Shan, one of China’s most seasoned and successful financiers, during a recorded video meeting with brokers held during the depths of Shanghai’s punishing Covid-19 lockdown. Shan added his Asia-focused private equity group PAG, which manages more than $50bn, had diversified away from China.

The unusually sharp criticism from Shan, long a vocal defender of Beijing, came at a critical time for the country’s capital markets. A regulatory crackdown in China has lopped roughly $2tn off the market value of listed tech groups over the past 12 months as Xi has railed against the “disorderly expansion of capital”.

In place of the open markets he talked about a decade ago, the environment for raising capital that has emerged in China is increasingly shaped by Xi’s broader strategic priorities — one that is focused on technologies considered central to economic competition with the west, directed by the state and tinged with suspicion about outside influences.

The shift reflects how foreign investor influence is fading as Beijing pushes forward with efforts to mould China’s equity capital markets into an assembly line that marshals private funding towards policy goals, with the ultimate aim of producing a new generation of national champions across strategic sectors.

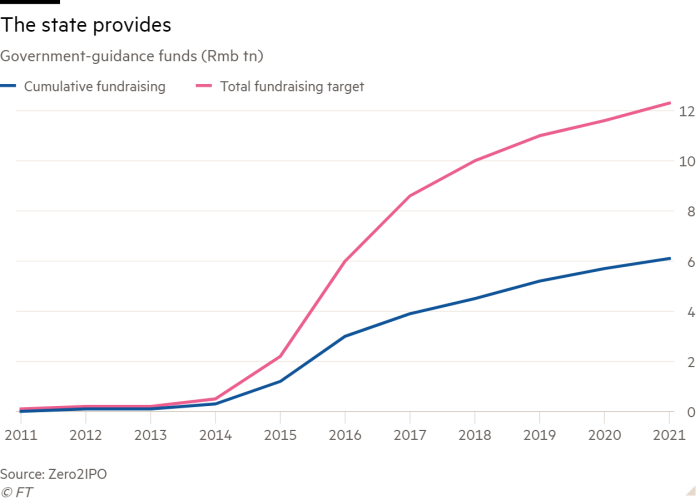

To that end, the state is expanding its presence up and down the country’s IPO pipeline. Over the past decade, so-called government guidance funds have raised more than $900bn to ensure enough early funding flows to companies from favoured industries such as high-end manufacturing, renewables and biotech. Additionally, policymakers have pushed through reforms to grant swifter listings as soon as such companies are ready to go public.

For Xi, funding China’s transformation into a global centre of high-tech innovation is central to national defence. In a speech published last year in the country’s top journal of Communist party theory, he warned that “only by grasping key core technologies in our own hands can we fundamentally guarantee national economic security, national defence security and other securities”.

“Investors are doing a reset,” said Kiki Yang, co-head of Bain & Company’s Asia-Pacific private equity practice. Gone are the days of disruptive start-ups burning through foreign backers’ cash to scale up for an initial public offering in New York or Hong Kong. “As a fund, we need to think about the sectors that can actually benefit from a policy perspective,” she added. “A lot of the bigger deals are [being] done by the government-led funds, at least in the last year or so.”

That is a far cry from a decade ago, when China’s start-up scene was flush with cash from private overseas investors including Sequoia and SoftBank, whose early backing for the likes of Alibaba and Tencent helped foster innovative apps and payment platforms that reshaped the Chinese economy.

Fraser Howie, an independent expert on Chinese finance, said the country’s leaders “don’t consider platform and internet companies as genuinely innovative. They want microchips, quantum computing, genetics, real tangible things as opposed to cyber space.”

Howie said US sanctions imposed on Chinese semiconductor and telecoms equipment makers and blowback in Europe over Beijing’s refusal to condemn Russia for the invasion of Ukraine have pushed the party-state to funnel more money to sectors it believes are vital to safeguarding national security and China’s economic ascent. “Xi Jinping is clearly dictating it,” Howie added. “The question is how successful he’ll be.”

Investors left out in the cold

Xi’s first big IPO intervention came in November 2020, when regulators scrapped what would have been the record $37bn listing of Ant, the fast-growing fintech group owned by billionaire Alibaba founder Jack Ma. But the broader regulatory crackdown on the tech sector began in earnest almost 12 months ago, shortly after ride-sharing app Didi Chuxing listed in New York despite warnings from Chinese regulators over data security concerns.

That prompted a halt to almost all offshore IPOs to allow regulators to finalise new foreign listings rules for companies with large amounts of user data. At the same time, tensions flared over Beijing’s refusal to grant US regulators full access to the audit reports of Chinese companies trading on Wall Street, raising the spectre of forced delistings and questions over whether selling shares in New York will be worth the trouble.

“The US is proving to be very, very difficult,” says the head of Asia equity capital markets syndicate at one Wall Street investment bank. The person added that there was “no doubt” that more Chinese IPOs would go to Hong Kong once Beijing allowed offshore listings to resume, but different types of companies would dominate deal flow.

“These very techy, platform, data-sensitive names are just hard to invest in,” the banker said. “The flip side is, if you bring a company [to market] that’s doing renewable energy in China, everybody knows that is a business model the government’s going to encourage.”

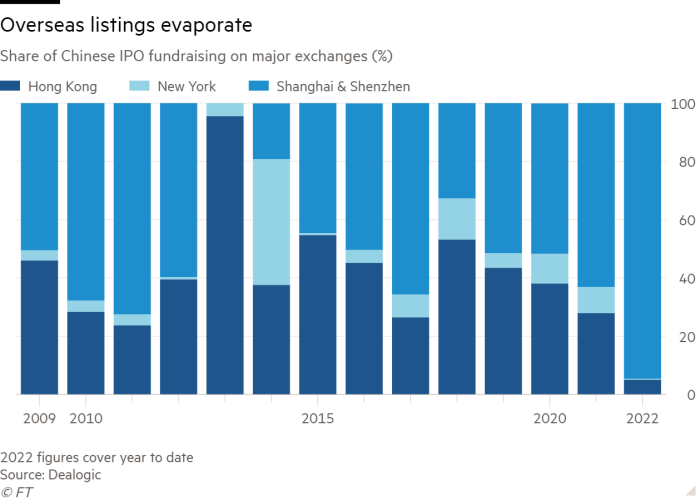

No one knows when offshore IPOs will return in full force. Data from Dealogic show 95 per cent of the $35bn in IPO fundraising by Chinese companies this year has been amassed in domestic markets, where state-run investment banks such as CICC and Citic Securities dominate deals and new share sales require regulators’ sign-off.

As a result, most listings now go to either Shanghai or Shenzhen, and few expect this to change any time soon. “What you’ve seen in the first quarter gives you a pretty good idea of what the rest of the year is going to look like,” said one veteran IPO lawyer with an international group based in Hong Kong. That would keep foreign investors largely shut out of Chinese IPOs, while top Wall Street banks such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley will miss out on Hong Kong and New York listings, which have delivered billions of dollars of annual fees in recent years.

In addition to curtailing access to global equity markets, the past 12 months have hastened changes further up the deals pipeline, where regulatory action and state-backed investment are having an impact on which companies receive the funding from venture capital and private equity groups needed to scale up for an IPO.

“Everyone knows how tough it is this year,” said Yang, at Bain. She estimated the level of undeployed funds held by Asia-focused investors rose to a record $650bn in 2021 as dealmaking in China was hit by investor concerns over geopolitical tensions with the US and tighter regulation.

But she added that while funding plummeted in the second half of last year for some segments of tech historically favoured by private equity, others, such as semiconductors, shot higher thanks in large part to government-led funds.

‘Tonnes of capital will be wasted’

The scope and ambition of government guidance funds have also grown substantially during Xi’s tenure. These public-private investment funds, set up by or for government agencies, carry a dual mandate of furthering Beijing’s policy aims and delivering financial returns.

Since the start of 2013, about 1,800 government guidance funds have raised more than Rmb6tn ($900bn) to invest in strategic sectors and have already received approval from regulators to bring in more than double that amount, according to estimates from independent research group Zero2IPO.

Figures from investment data provider Preqin show the share of China-focused private equity and venture capital fundraising going to state-led funds has risen from about 2-3 per cent prior to Xi coming to power to more than a third in recent years. Bain estimated about 40 per cent of the more than $86bn raised by foreign and domestic China-focused funds last year went to these state-backed funds.

“The vast majority of funding into Chinese VCs is from the government,” says William Bao Bean, a general partner at global venture capital firm SOSV. He said that while “the smart money in China has traditionally been global capital”, investing has become much more difficult over the past four years as government controls have grown more stringent.

The resulting shift in funding has produced more IPOs by companies from what Beijing has designated “strategic emerging industries” including electric vehicle manufacturers, biotechnology, renewable energy, artificial intelligence, semiconductors and other high-end equipment manufacturing.

In 2020, such listings accounted for more than half the value of equity…

Read More:How Xi Jinping is reshaping China’s capital markets

2022-06-12 04:02:00