MCCAIG/iStock via Getty Images

Introduction

The government agencies regulating the short-term credit markets have actively sought to create a market structure that meets their objective – government stabilization of the riskiness of short-term credit markets. Every crisis seems to blow these markets to smithereens. And the taxpayer foots the repair bill afterward.

But a private-sector solution to the instability of the short-term credit market structure can be established, free from taxpayer-financed periodic government bailouts. Creating a market that improves private-sector market stability, this structure can also provide greater value to investors. And the burden of credit risk is transferred from taxpayers to private risk-takers.

I recently described a way to provide retail investors with direct access to short-term Treasury markets. A second following article considered a similar way for retail investors to access credit-risky debt markets. These short-term debt access portals offer two advantages compared to the Prime Money Market Funds (MMFs).

- They are more suitable for retail investors.

- They are less likely to collapse when markets are under stress.

Terms

LIBOR. A daily index of credit risky short-term rates, provided by a panel of 18 large commercial banks, is being retired. The basis for the index was an estimated deposit rate (the interest rate on wholesale dollar 3-month deposits in London). LIBOR reflected the fact that short-term credit risk was real.

SOFR. The governmentally micro-managed secured overnight financing rate (SOFR). The Fed computes SOFR daily from repo rates collateralized by Treasuries other than special issues. SOFR is the lynchpin of the government’s newly designed short-term credit market structure. This structure replaces the government’s direct acquisition of short-term debt during the post-financial crisis quantitative easing program. SOFR reflects the new world of government transfer of credit risk from investors to taxpayers.

Quantitative easing. Post-Financial Crisis, the Fed reinforced its initial economic stimulus, a policy rate set to zero, with the added stimulus of aggressive purchase of securities. In this program, the Fed bought hundreds of billions of dollars in assets, mostly U.S. Treasury securities, federal agency debt, and mortgage-backed securities.

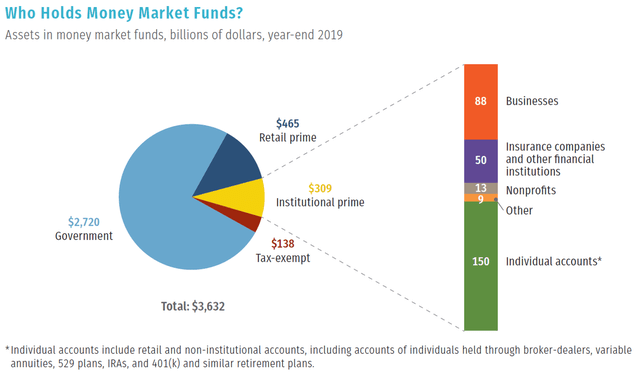

Prime MMFs. A prime money market fund is a type of investment fund that invests in high-quality, short-term debt instruments, cash, and cash equivalents. It is suitable for institutional investors.

AMLFs. During the Financial Crisis, the Fed bailed out the prime money market funds with the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF). The AMLF was a lending facility that provided funding to U.S. depository institutions and bank holding companies to finance their purchases of high-quality asset-backed commercial paper from money market mutual funds under certain conditions.

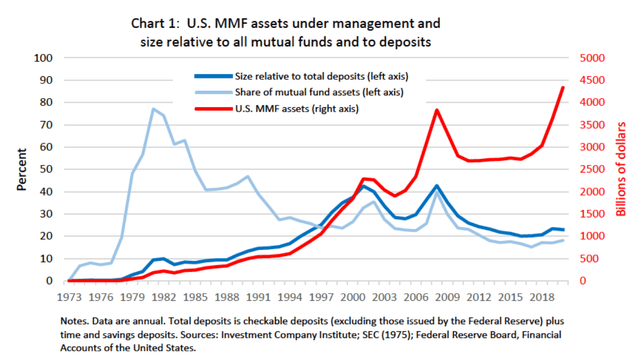

Volume of MMFs over time (Investment Company Institute. SEC, Federal Reserve Board)

MMLF. The Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF). A lending facility to backstop the money-market mutual-fund sector was introduced by the Fed at the outset of the COVID Crisis. It made loans available to eligible financial institutions backed by high-quality assets purchased by the institutions from money-market mutual funds.

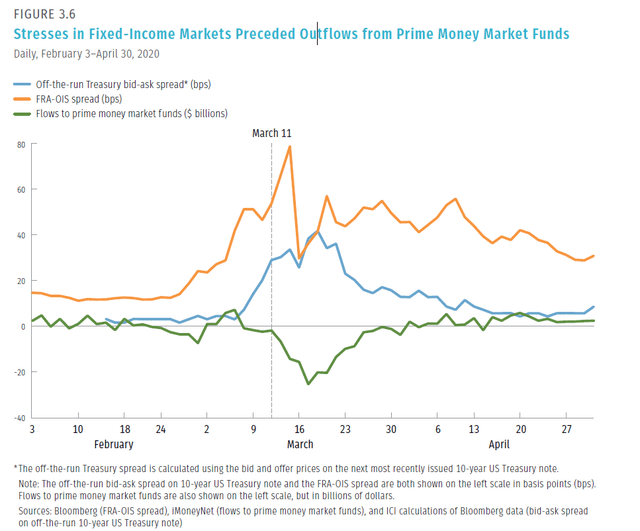

The graph below measures withdrawals from MMFs during the Covid Crisis, reflecting the market effect of MMLFs.

Timing of COVID stress (Bloomberg)

Prime money market funds tend to fail when the markets are under stress. In response to unfolding crises that shook the Fed’s frail SOFR-based fix, the Fed cosseted SOFR with government bailouts as crises unfolded, and market interventions that were activated when the short-term rates targeted by the Fed varied from Fed objectives.

The status quo

The old short-term market structure was based on two primary channels through which money flowed from investors to debtholders – commercial bank deposits and prime money market funds.

The first channel, wholesale deposits, has been squeezed to a trickle by the end of LIBOR and regulatory disincentives to banks offering wholesale bank deposits. That has meant that direct corporate debt issuance, intermediated by investment funds, now takes center stage. The graph below compares the holdings of MMFs to other mutual funds and deposits.

Who holds MMFs (The Investment Company Institute)

Prime money market funds tend to fail when the markets are under stress. In response to unfolding crises that shook the Fed’s frail SOFR-based fix, the Fed cosseted SOFR with government safety measures as crises unfolded. They were market interventions that were activated when the short-term credit funds threatened to collapse.

The federal short-term credit package

What is the appropriate financial market response to the passing of LIBOR? Is it reasonable to access the government balance sheet to bail out the entire short-term corporate debt market during recurring crises? Is a taxpayer bailout of private debt whenever it is threatened appropriate? The assurance of a bailout of corporate debt in every crisis amounts to a taxpayer guarantee of all short-term corporate borrowing.

There has been no private-sector effort to replace these extreme federal measures to date. The article proposes a long-term alternative to the government-directed solution to the LIBOR replacement problem. Its advantages are that it is free of ad hoc government market intervention and that it depends on the credit markets to fix themselves.

The lynchpin of the regulators’ new version of the short-term debt market structure is SOFR. The government-created SOFR index fails in two ways.

- SOFR is backward-looking. Witness for example the currently still trading three-month March SOFR futures. May 17th open interest was nearly $500 billion in a futures contract that forecasts the past.

- SOFR includes no credit risk dimension. SOFR is constructed from rates on repos that are collateralized by Treasuries. Thus, there is no discount applied to these repos for credit risk.

The underlying intent of post-LIBOR Fed responses to crises is to inspire confidence that high-grade commercial paper is less risky than before. Where once private-sector borrowers signaled their forecasts of risk with LIBOR, the market regulators signal their intent to eliminate this risk at taxpayer expense with SOFR. SOFR is a credit-risk-free rate appropriate to the government’s spanking new credit-risk-free corporate commercial paper market.

A market-based alternative to the bailout-based federal system

A key benefit of this market innovation is to reduce the need for the now-commonplace Fed bailouts of credit markets, by creating a stable private-sector system of credit risk management.

A better version of LIBOR. In addition to governmental defenses against hazards in the short-term credit markets, it would be desirable to add the kind of private sector credit risk indicator that LIBOR once provided. This index should avoid the failings of SOFR by providing a forward-looking interest rate index that includes the market estimate of the costs of expected credit risk.

Characteristics of LIBOR to keep.

- Homogeneity. LIBOR summarized the average cost of credit risk for the entire high-quality short-term private market at a three-month maturity.

- Reliability. LIBOR was stable, providing its information when the population of borrowers with market access declined.

- Relevance. LIBOR was a forward-looking credit-risky rate.

- Liquidity. The key strength of LIBOR was its associated highly liquid Eurodollar futures market.

A characteristic of LIBOR to throw away.

- Opinion-based index. The primary failing of LIBOR was that it was not derived from market transactions. However, deriving a daily index composed of market transactions in the private short-term debt market is no easy thing. The commercial paper market has no liquidity.

In summary, the market ought to manufacture a homogeneous, reliable, relevant, index based on transactions in a liquid market for a single commercial paper-based instrument. No such instrument exists.

How would a private sector LIBOR replacement work?

For a new credit-risk index to be reliable, it must be provided by a stable reliable credit-risky instrument and marketplace.

The instrument would necessarily be a prime commercial paper-backed security. To be market-priced continuously the instrument ought to have the negotiability property of an ETF.

In past articles, cited above, I have described closely related exchange-traded instruments. The key characteristic of their market structure is that liquidity is created by the separation of trading from settlement. A virtual version of the physical instrument is traded. Settlement of the traded instrument is a periodic (weekly) event. Once settled, the instrument becomes commercial paper-backed debt.

This PowerPoint deck explains how virtual trading interacts with a settlement.

Read More:Post-LIBOR Short-Term Debt Markets – Government Overreach

2022-05-23 04:14:00