This story is about how America defeated the Nazis. This is the origin story of critical race theory, the great migration and the civil rights movement. It’s also the tale of the first Black member of a presidential cabinet, peace in the Middle East and how a Black woman took the infamous Caucasian phrase “one of my best friends is Black” and used it to recruit, organize and form a coalition of brilliant Black minds that would change Black America forever.

It’s no secret that President Franklin Roosevelt was racist. To be fair, when he was elected in 1936, racism was almost a prerequisite for being CEO of America, Inc. Roosevelt’s predecessor was so racist that Black voters said: “To hell with this party,” making Herbert Hoover the last Republican presidential candidate to win the Black vote. Roosevelt was still a bigot, though. He put Hugo Black, an inexperienced Klansman, on the Supreme Court. He invited the white Olympic champions to the White House but snubbed Jesse Owens after what still stands as one of the Olympic performances of all time. He refused to support anti-lynching legislation, signed an executive order interning Japanese Americans and wasn’t very concerned with the Holocaust. Perhaps Mary McLeod Bethune was the only one who could speak to FDR in the African-American dialect known as “keeping it real,” for one reason:

Eleanor Roosevelt loved her some Mary McLeod Bethune.

Eleanor and Bethune’s friendship predated Roosevelt’s presidency and Bethune even chilled at FDR’s mama’s house, so he had no choice but to respect the relationship between his cousin/wife and Bethune. Plus, he rarely came in contact with people of the negro persuasion, so when the president tapped Bethune as the director in the National Youth Administration’s Division of Negro Affairs, he believed her when she told him that the Black scholars she knew were actually more intelligent than the white boys in his administration. Bethune convinced Roosevelt that, if he tapped into this genius for an actual Black agenda, Black voters who traditionally voted for Republicans might be willing to switch their support to the Democratic Party. As racist as he was, Roosevelt was also a politician.

He took up Bethune’s offer and had her organize a group of the most innovative Black thinkers in the country, who eventually became known as the Black Cabinet, the Black Brain Trust or the Federal Council of Negro Affairs. Although the group was not an official government entity (they took no notes and usually gathered in Bethune’s apartment or her office as a backchannel on policy for Black America), these brilliant men and women collaborated on legislation, economic development and, in many cases, penned the laws that would affect Black Americans throughout the country.

In the mid-1930s, when Roosevelt became president, white folks were doing badly. To lift America out of this Great Depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal created massive economic programs sponsored by the federal government. Programs like the new Social Security Administration gave people financial security, the Works Progress Administration gave people jobs, and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) refinanced mortgages at low-interest rates to prevent foreclosures. Although Roosevelt’s New Deal built what we now call “the middle class,” the most significant government program in the history of this country largely excluded Black people.

Lawrence Oxley, a professor at historically Black St. Augustine College, appointee to the Department of Labor and one of the Black Brain Trustees, wanted in on the deal. He gained control of North Carolina’s Division of Negro Relief and created a program for unemployment relief and this crazy idea called the “Black minimum wage,” which was eventually adopted by the Roosevelt administration. Outside of his job in the Labor Department, he began writing articles explaining how Black people could take advantage of these new programs. He and Bethune convinced the president to set aside 300,000 public works jobs for African Americans and devote 10 percent of the WPA’s spending to African Americans.

When the Black Cabinet somehow convinced Franklin Roosevelt to include funds for interviewing former slaves for the Federal Writers Project, Hampton University professor Roscoe E. Lewis ensured that “the Negro [was] not neglected in any of the publications written by or sponsored by the Writers’ Project.” The Negro in Virginia interviewed ex-slaves and traced the history of enslaved Africans in America from 1619 through the Reconstruction from a Black point of view.

Before Crystal Bird joined the Black Cabinet as race relations adviser to the Office of Civilian Defense, she had already met activist and civil rights activist Arthur Faucet. After the two married and she became the first Black woman elected to the Pennsylvania legislature, Roosevelt needed Faucet and Bethune to talk to one of the most revolutionary rabble-rousers in America, Asa Philip Randolph.

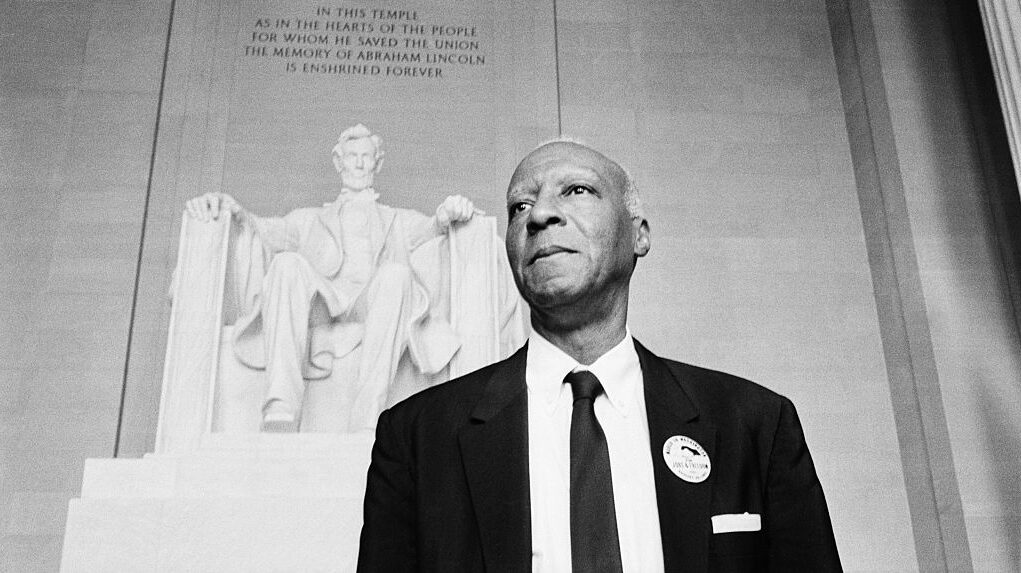

A. Philip Randolph was always up to something.

A socialist union leader and an unapologetic radical, Randolph wasn’t a member of the Black Cabinet. Still, the Brain Trust knew the power and influence he wielded among the Black working class. Roosevelt was kinda preoccupied with this little thing called World War II, so he dismissed Randolph’s threats of a large-scale protest in Washington until the Black Cabinet told the president: “Trust me, you wanna listen to ol’ boy. He don’t play.”

One day before Randolph’s big protest in the nation’s capital, Roosevelt met with Randolph and put the Black Cabinet in charge of addressing the issue of discrimination in the workplaces of defense contracts preparing for World War II. Howard University professor Rayford Logan, another member of the Brain Trust, drafted Executive Order 8802, declaring that “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in the defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” The order didn’t just enforce equality in the defense industry; it would eventually lead to the wholesale desegregation of the American military and shift the demographics of the American map.

The Smithsonian’s American Experience notes:

“The mobilization of the American wartime economy in 1942 produced more than $100 billion in government contracts in just six months, creating a plethora of new job opportunities in the North, the predominant area of manufacturing. Industrial hubs such as New York City, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Detroit were attractive due to the number of jobs available to blacks. Over 1 million African Americans would join the workforce during World War II. Industrial jobs were particularly appealing to younger African Americans because of the assistance they could receive through free government training programs sponsored by the National Youth Administration. The agency, part of the Works Progress Administration, aimed to train and educate American youth, ages 16-25.

Historians now call it “The Second Great Migration.”

With such a momentous victory under their belt, one would assume the Black Cabinet would leave well enough alone. “But more can be done,” Bethune wrote in a letter to Roosevelt on November 27, 1939. “One of the sorest points among Negroes which I have encountered is the flagrant discrimination against Negroes in all the armed forces of the United States. Forthright action on your part to lessen discrimination and segregation and particularly in affording opportunities for the training of Negro pilots for the air corps would gain tremendous goodwill, perhaps even out of proportion to the significance of such action.” The Black Cabinet didn’t just make the suggestion that Roosevelt introduce Black pilots to the Army’s newly created “Air Force,” they went ahead and did it themselves.

Among the Army’s top brass, Black pilots flying airplanes was an insane idea. There hadn’t been an African-American pilot in the history of the U.S. Armed forces. And if you thought white people hated seeing uniformed Black soldiers being treated as heroes after World War I, can you imagine how furious they were about Black pilots flying the most sophisticated aircraft in the world? Commanding officer Henry “Hap” Arnold was in dire need of pilots but admitted that a crew of African-American airmen “would result in Negro officers serving over white enlisted men, creating an impossible social situation.” Arnold added that, since the Armed Forces were segregated, there was no place to train them and no funds to build an entirely new training facility.

The July 1940 cover of the NAACP’s publication The Crisis illustrated the betrayal Black American’s felt: “Warplanes: Negro Americans may not build them, repair them, or fly them, but they must help pay for them.” However, the Black Cabinet was fine about the Army’s decision…because they had already found a solution. Unbeknownst to most of America, the Black Cabinet had privately convinced the White House to tack a benign provision—Public Law 18—onto a military appropriations bill intended to prepare the nation’s armed forces for…

Read More:The Beautiful Minds: The secret history of the Black Brain Trust

2022-02-02 19:16:47